OUR STORY

In 1960 when we first conceived the idea of our Fayetteville property at 4618 N. College, we saw it as a place for community and regional family recreation.

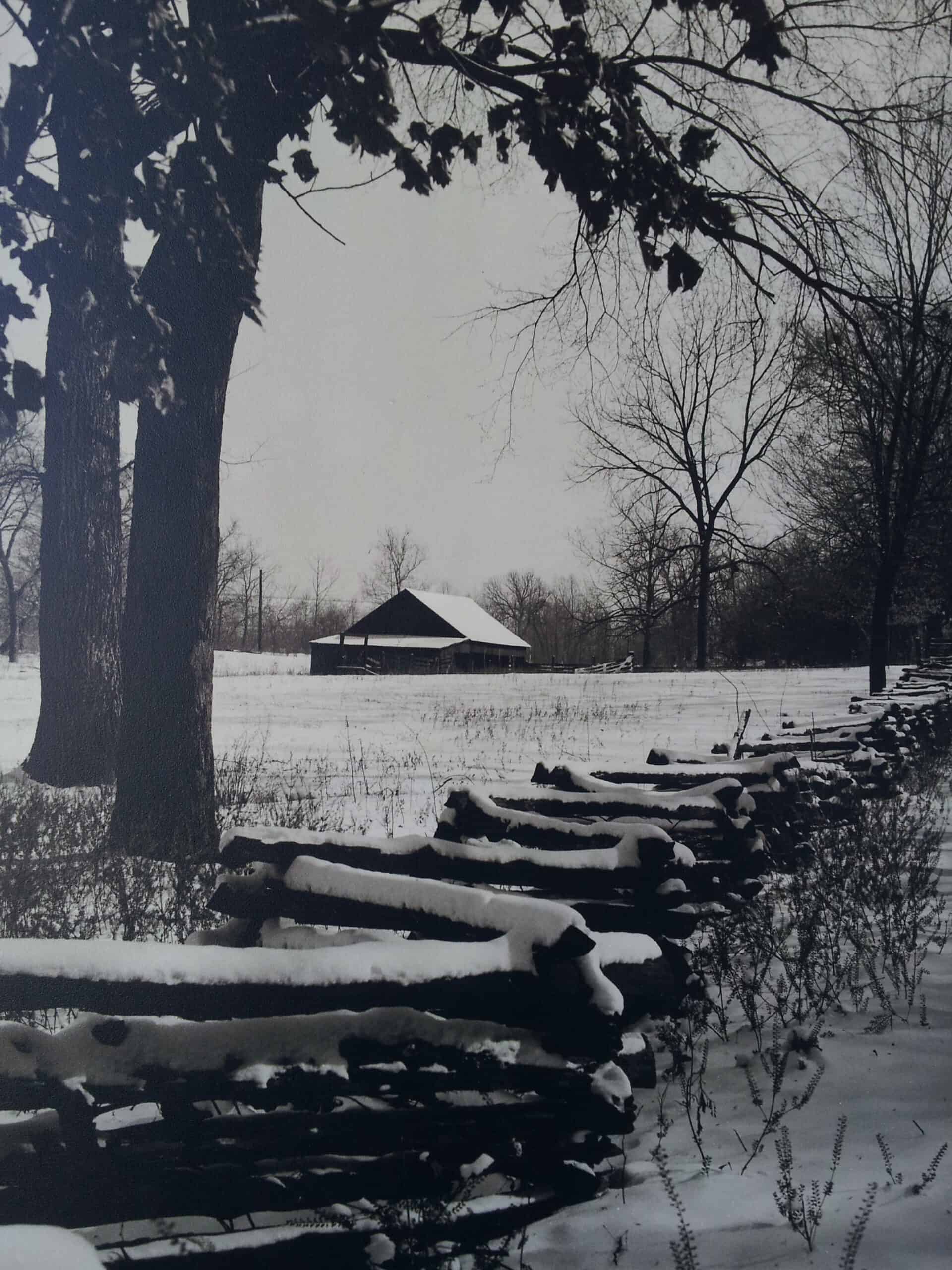

Our founders, Henry T. (Tommie) and Virginia Haseloff, took a piece of over grazed eroded farmland and shaped it into a beautiful property. They created a lake from a shallow creek for beauty, water rides, and water retention. They added a stable for horseback riding, a golf driving range for the public, and a free area for family picnics, reunions, and corporate events. Among out guests at Hillbilly Holler were sports celebrities and John and June Cash who drew a record crowd for Winthrop Rockefeller as he ran for governor.

In the 70’s when the property was divided between partners, sold, and given for highway improvements and easements, our recreational offerings changed. One part became Lokomotion, United Bilt Homes and Southtown Sports. The fifteen plus acres were retained as Hog Heaven, Inc. continued the golf driving range, display lot, farmstead, and natural area.

In the late 90’s, we offered 2.5 acres to Hillborn Heritage Foundation, a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization, for a heritage farm. The group had seen the financial and ethical problems of their original purpose, building a zoo. Their attention turned to preserving heritage animals and plants that had a long relationship with man. These animals are as threatened in contempory factory farm agriculture as wild animals are threatened by encroachment. Although that project was not complete, we took an abiding interest in the farm, a return to the origin of our property.

In March 2009, we began moving into a recreational phase appropriate for this time. Mae Farm is now an interwoven working family farm that provides an agritourism experience to others. We did a lot of thinking, research, and planning. We cleaned up the old place, built line fences, started renovations, added more power, put utilities underground, and rediscovered the sewer line. In the midst of a drought, we made our first gardens and plantings. We worked to identify and support our native plants and animals. We added food services. In 2014, we hosted 12,000 guests for the Fayetteville Chamber of Commerce sponsored Northwest Arkansas Hispanic Heritage Festival. This year we will build run-ins, interior fences, and add our first heritage horses. We continue looking for better ways to fulfill our mission and to serve our guests. WE ARE A FARM IN PERFORMANCE.

Our mission is to enjoy life and glorify God by building something good and positive. For us that something is an interwoven working family farm that:

- nurtures native plants and animals and their habitats,

- conserves heritage livestock breeds and heirloom plants,

- provides cultural continuity of American traditions and values and those of our family, and

- shares our experience through education, events, equine activities, and wholesome products.

HISTORY & BACKGROUND

The first record of this land in the Arkansas wilderness is Choctaw Scrip Certificate No. 2 to Ish-to-nan-chi for 320 acres at the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek in September 1830. The treaty was a removal agreement between the Su-quak-natch-ah and other clans of Choctaw Indians and the United States. The Choctaw were to leave Mississippi for Arkansas Territory.

The claims were not settled for twelve years. In pursuance of the provisions of an Act of Congress on August 23, 1842, the Secretary of War provided for the satisfaction of claims arising under the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek. Finally in August 1846, a subsequent financial appropriation and a Joint Resolution of Congress authorize the Secretary of War to adjudicate the claims of the Su-quak-natch-ah and other clans of Choctaw Indians, whose cases were left undetermined by the Commissioners for the want of the Township maps.

Joseph Lawrence Dickson, a [proxy/”proxee” (6)] of Way-la-ho-nah and Cun-ne-to-nah representatives of Ish-to-nan-chi, by then deceased, had deposited in the GENERAL LAND OFFICE of the United States, a Certificate of the REGISTER OF THE LAND OFFICE at Fayetteville, Arkansas whereby Choctaw Certificate No. 2 in the name of Ish-to-nan-chi for three hundred and twenty acres of land was surrendered to Joseph L. Dickson, his heirs and assigns forever.

James Buchanan, 15th President of the United States of America, caused these Letters to be made PATENT, and the SEAL of the GENERAL LAND OFFICE to be affixed at the CITY OF WASHINGTON, April 1, 1857, the eighty first year of the Independence of the United States.

It is unlikely that Ish-to-nan-chi or his heirs ever saw or lived on the land in Arkansas. The Choctaw travelled by steamboat to Little Rock, and then to Ft. Smith and Oklahoma. We do not know what the heirs received for the land. We do not know what the role of Joseph L. Dickson was except he identified the land. We know that after all that time, the land became his with “all rights, privileges, immunities, and appurtenances of whatsoever nature thereunto belonging.” He was free to sell it. (See #On Speculation)

So the 320*** acres was slowly divided, sold, and resold coming down through many lives to us today through the purchase of Henry Thomas [Tommie] Haseloff. He began acquiring the land or our portion of it in 1959. Tommie was a real estate broker who had worked as a young Texan in California. He believed that Northwest Arkansas would grow and develop too. Land between the cities was in the path of progress. Tommie wanted out of the real estate business, and the land provided the way.

One of Tommie’s former salespersons, Vera Harper Alison, owned this property. They struck a deal for 36 acres: $1000 an acre, nothing down, $200 a month payment. A thousand dollars an acre was an incredible price for a piece of eroded, overgrazed rocky cow pasture when bottom land was selling for $300 an acre. And there was the dam. One lawyer said he always speeded up when driving by in case the dam broke. So Tommie’s deal was a joke to many.

But to our family, the land became the purpose and source of our life—keeping it, paying the mortgage and taxes, taking our income from the land to pay for everything, education, everyday things like food and clothes, and whatever else we acquired. Everything came from the land and our labor on it. Much was sacrificed, much lost, and gained, three lifetimes measured.

Tommie retired after 44 years in the driving range business, a holding action, the land speculation business in reality. Tommie’s deal was now genius. Yet he could never sell the land. “Capital gains,” he said. In truth the land had become a family member.

Robert Frost wrote a poem that says, “The land was ours, before we were the lands.” That was certainly the truth for this family. We owned it yes, scraping and cussing and struggling to pay for it. But over three lives and sixty plus years, we became the lands. We loved it as its children now. The last of us has taken the Steward’s Oath to its future.

On Speculation:

Land speculation has always existed where there are vast stretches of seemingly unclaimed land. People seek their fortunes in acquiring and selling land. The limitless tracts of America given by the Kings of England or Spain or France to patrons or to commercial ventures drew both greedy and visionary men. William Penn received 45,000 square miles of land in payment for the debts of King Charles II. He established Pennsylvania, a Quaker model of religious freedom and fair Indian relations, a proprietary colony. The Virginia Company was a joint venture commercial company looking for gold and silver, but finding tobacco instead. Speculators, readers of men, knew that it is in the heart of men and women to own their own land and build their dreams on it. Every new generation sees the value in land increase and fears they will miss their opportunity.

Arkansas had several men who speculated in land on a large scale. John M. Ross, Arkansas’s largest speculator cashed in scrip for 16,910 acres. Joseph Holcomb, Springdale, the second largest speculator cashed scrip for 7,680 acres. William E. Woodruff who ran a land agency in Little Rock, hired out his services to other scrip holders, but also acquired 1340 acres for himself in Pulaski County. We know that Joseph L. Dickson in Fayetteville cashed the scrip, Certificate No. 2 for the 320 acres which was the origin of Mae Farm. The scrip or vouchers for new land had little meaning for the Choctaw who had lost their homeland**, but it made the Arkansas men’s fortunes. As their lives and memories faded, people in the growing cities still give directions by Holcomb or Dickson Streets. [Link]

**Today it is trendy to say property is not worth fighting for or dying for, as if it is trivial, easily replaceable, fungible. There is a self-righteous superiority and ignorance in such thoughts. But such thoughts are ill informed. All property is bought with a price beyond money — the hours, days, years of our lives, our work, our sacrifices, our dreams. Since time is not a renewable resource, what is given is gone without the land on which it was spent. If the fruit of our labor is not our own, bought with our lives, passed to our children, we are slaves working for masters.